|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

About 1600 B.C. there appeared a bronze-age culture, which came to be embodied in Chinese history as the Shang dynasty. Most of what we today know about this civilization derives from excavations at its capital Anyang in Hunan, carried out for the most part in the years between 1929 and 1933. Through most of the second millennium B.C., the lands along the Yellow River in northern China were ruled by

the Shang (sometimes also called Yin). The Shang kingdom seems to have been built upon a group of city-states under the nominal rule of a high king, who in all probability could not exert much direct authority over the farther reaches of his territory. So far as can be made out, the social organization of the Shang time is best described as a kind of proto-feudalism. As mentioned before, the area under the jurisdiction of the king quite probably was small, perhaps not more than 100-200 miles in any direction from Anyang. Traces of a family ruling system and of ancestor-worship are discernible. Furthermore, matriarchal traces, noted by various authorities, seem to have given place, during this period, to a rigidly patriarchal society.

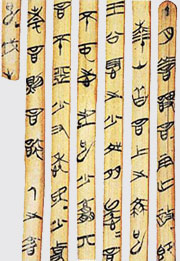

The Shang dynasty had writing, some of which survived incised on tortoise shells and ritual divination-bones. What its literature might have been like can merely be

guessed. In later ages, many authors created poems, songs and speeches that they attributed to the Shang. Therefore, such pieces belong to the historical imagination and creation of later ages rather than to Shang writers themself. The oracle-bones were employed for a method of divination, the so-called “scapulimancy”, which seems to have been peculiar to the cultural area in question. It consisted in heating the shoulder blades of mammals or the carapaces of turtles, the reply of the gods being designated by the shape, the size and the direction of the cracks produced. There were two kinds of replies: 1) “yes or no”, and 2) “lucky or unlucky”. In general, the answers were not inscribed on the bone beside the questions, as the shape of the cracks would indicate them, but sometimes the subsequent verification of a prophecy was recorded. Among the most important questions asked in the course of such rituals were: a) to what spirits or deities certain sacrifices ought to be made, b) travel directions generally; in particular, where to stop and how long, c) matters regarding hunting and fishing, and problems concerning d) the harvest, e) the weather, f) illness, recovery and health.

The last century of the second millennium B.C. saw the rise of a new domain, the Zhou, to the west of the Shang heartland. In 1020 B.C. the Zhou threw off their subordination to the Shang ruler and conquered his vast lands. A small kingdom suddenly found itself in possession of large territories, and to administer those provinces, members of the royal house were sent out to preside over feudal domains throughout northern China. The Zhou feudal system was conceived as a family working together. In the future, this model was to have lasting consequences in whole China. Little is known of the origin of the Zhou people, except that they were from the western regions - in the present provinces of Kansu and Shensi - and that they were less advanced culturally than the Shang, whom they admired. Their conquest of the Shang area (Yellow river valley, parts of the North China plain, lands between the Huang-Ho and the Huai River) took place at a time fairly close to the Aryan conquest of India. The outstanding feature of the Zhou period certainly was its systematization of bronze-age proto-feudalism that had been sketched out under the predecessors, until it became almost as fully developed as in the typical feudal period of Europe. The empire was partitioned into fiefs, which were held by a new aristocratic class. The whole system rested on agricultural production, in which corvée-labour of the peasant-farmers on the lord’s land was a prominent feature.

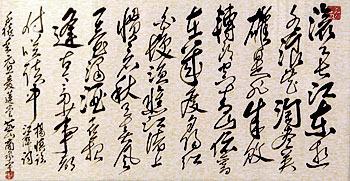

The Zhou continued the Shang traditions of bronze working (for all kinds of uses: ritual, war and luxury), pottery and textiles, and took further steps in the development of the written language. During the early centuries of Zhou rule, writing was principally used for divination, furthermore for commemorative inscriptions in ritual vessels and for basic recordkeeping. There were two groups of works that were handed down orally and circulated through the domains of the Zhou. While conserving early material, both kinds of works were open and could be added to and varied over the centuries. The first of these consisted of sayings and speeches that supposedly came from the early kings, offering guidance in the principles on which the Zhou polity was founded. This became the so-called “Classic of Documents”

(Shu-jing). The second was a body of over three hundred poems that became the “Classic of Poetry” (Shi-jing). The so-called “Classic of Poetry” contained ritual hymns and ballads that were supposed to date back to the beginning of the dynasty, along with more recent poems from the 8th and 7th centuries B.C. The early “Classic of Poetry” are hymns used in dynastic rituals to address the deified spirits of the founders of the Zhou Dynasty, the mythical kings Wen and Wu. The corpus of the “Classic of Poetry” can be divided into four fragments: 1) the Hymns (Song), 2) the great Odes (Da-ya), 3) the lesser Odes (Xiao-ya), and 3) the Airs (Feng).

The following poem is from the Da-ya section and recounts decisive episodes in the founding of the Zhou Dynasty. It illustrates the particular relationship between poetry and politics in early Chinese history. “She Bore the Folk” tells the story of the miraculous birth of Lord Millet (Hou Ji) who created agriculture and whom the Zhou royal house revered as their ancestor.

“She Bore the Folk”

“She who first bore the folk- Jiang it was, First Parent. How was it she bore the folk? She knew the rite and sacrifice. To rid herself of sonlessness She trod the god’s toe print And she was glad. She was made great, on her luck settled, The seed stirred, it was quick. She gave birth, she gave suck, And this was Lord Millet.

When her months had come to term, Her firstborn sprang up. Not splitting, not rending, Working no hurt, no harm. He showed his godhead glorious, The high god was greatly soothed. He took great joy in those rites And easily she bore her son.

She set him in a narrow lane, But sheep and cattle warded him. She set him in the wooded plain, He met with those who logged the plain. She set him on cold ice, Birds sheltered him with wings. Then the birds left him And Lord Millet wailed. This was long and this was loud, His voice was a mighty one.

And then he crept and crawled, He stood upright, he stood straight. He sought to feed his mouth, And planted there the great beans. The great beans’ leaves were fluttering, The rows of grain were bristling. Hemp and barley dense and dark, The melons, plump and round.

Lord Millet in his farming Had a way to help things grow: He rid the land of thick grass, He planted there a glorious growth. It was in squares, it was leafy, It was planted, it grew tall. It came forth, it formed ears, It was hard, it was good. Its tassels bent, it was full. He had his household there in Tai.

He passed us down these wondrous grains: Our black millets, of one and two kernels, Millets whose leaves sprout red or white, He spread the whole land with black millet, And reaped it and counted the acres, Spread it with millet sprouting red or white, Hefted on shoulders, loaded on backs, He took it home and began this rite.

And how goes this rite we have? At times we hull, at times we scoop, At times we winnow, at times we stomp, We hear it slosh as we wash it, We hear it puff as we steam it. Then we reckon, then we consider, Take Artemisia, offer fat. We take a ram for the flaying, Then we roast it, then we sear it, To rouse up the following year.

We heap the wooden trenchers full, Wooden trenchers, earthenware platters, And as the scent first rises The high god is peaceful and glad. This great odor is good indeed, For Lord Millet began the rite, And hopefully free from failing or fault, It has lasted until now”.

(Sources: An Anthology of Chinese Literature. Beginnings to 1911. Edited and Translated by Stephen Owen. New York, London 1996, p.12ff. Needham, Joseph, Ling, Wang. Science and Civilisation in China. Volume I: Introductory Orientations. Chapter 5: Historical Introduction, The Pre-Imperial Phase. Cambridge 1954. p. 73-100)

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||