|

|

|||

|

Confucius believed that a person’s potential for achieving moral rightness in all varieties of a lifetime’s actions and situations was an essential part of his or her natural endowment. According to his understanding, the cultivation of rightness through the dynamics of interpersonal conduct and its realization in the social and political spheres enabled people to integrate themselves into the cosmic order and to participate in a universe essentially defined by moral. This was the so-called “Way” of human beings. The process of attaining and consummating this Way in government and society must begin at the top with the ruler’s commitment to self-realization. Furthermore, Confucius believed that all people were similar by nature, and that their disparity basically was a matter of instruction and discipline. Since the natural gifts of each person were considered as consistent, it followed that at least in terms of individual capacity people had the same possibilities of realizing the Way in their social relationships and governments.[2]

The Master said“If anyone could be said to have effected proper order while remaining inactive, it was Shun. What was there for him to do? He simply made himself respectful and took up his position facing due south”.[3]

Although commonly regarded as a decidedly Taoist concept, wu-wei does play an important role in Confucian political theory. According to the classical Confucian attitude towards government, the ruler does not attend to matters of government. By setting a positive example and through the charismatic influence of his virtue, the people are led into a manner of conduct in which they seek moral achievement. The ruler, then, cultivating and giving expression to his fundamental endowment, serves as an example for others to follow in the development of their own natures.

Chi K’ang Tzu asked Confucius about government, and Confucius replied: “Government is rectification. If you lead with rectitude, who would dare be otherwise?”.[4]

The Confucian ruler, regulating his conduct so that his activities reflect a commitment to the expression of his moral nature, is able to influence and transform his people. This is the political principle of the guidance and transformation of the people through moral example. The ruler “does nothing” inasmuch as his personal cultivation, possible only through interaction with his people, doesn’t require the use of arbitrary demands on his subordinates. His relationship with the population is characterized by a total absence of compulsion and arbitrariness. That the particular realization of the people happens to be congruent with that of the ruler is due to their common involvement in the creation of a moral order.

People are similar to each other in terms of nature, but differ greatly as a result of practice.[5]

Since in Confucian ethical theory morality is entirely natural and intrinsic, it is not necessary for the ruler actively to augment the character of his subordinates in order to achieve social and political order. Rather, it is a matter of his participating with them in the realization of the incipient virtue which is already theirs by nature. Both, the ruler and the people pursue the consummation of their natural possibilities in a kind of dialogue. The subordinate looks to the ruler as a model of human potential, a model of what he himself can achieve. It must be stressed that – in this way of thinking - the place of the potential for cultivation and signification is and remains the individual. In the ideal relationship between individual and ruler, neither imposes on the other or elicits from him anything which is inconsistent with his own natural development. Although the term wu-wei is not used very often, its concept describes the ideal Confucian ruler appropriately as one who reigns but does not rule.

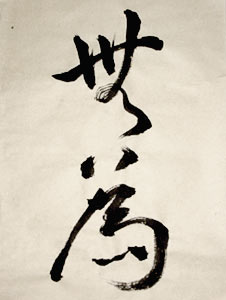

Sources: Ames, Roger T. The Art of Rulership. A Study of Ancient Chinese Political Thought. New York 1994. Hsia Kung-ch’üan. A History of Chinese Political Thought. Translated by F. Mote. Vol. 1. Princeton 1979, Calligraphy: www.cs.ust.hk

[1] The Chinese word Wu-Wei can be translated as „non-action“, “doing nothing”, or “acting naturally”. [2] Ames, p. 2. [3] Analects 31/15/5; cit. Ames, p. 28. [4] Analects 24/12/17; cit. Ames, p. 28. [5] Analects 35/17/2; cit. Ames, p. 33.

|

|||

|

|

|||